The upstairs garllery at the Sullivan Street Playhouse.

The upstairs garllery at the Sullivan Street Playhouse.

Lore Noto

producer

LORE NOTO, in costume to play the role of The Boy’s Father, receives a visit from Helen Hayes.

Lore Noto, the former commercial artist and sometime actor who produced THE FANTASTICKS, jokingly refers to the Off-Broadway musical as a “life sentence.” Since the show is completing its 41st year, his affliation with the Tom Jones/Harvey Schmidt creation does look like a lifetime commitment.

THE FANTASTICKS started slowly after opening to rather mixed notices in 1960. Noto carefully and expertly nurtured it and eventually was offered opportunities to take it uptown to Broadway. Had he done so, THE FANTASTICKS would probably be a regular statistic in the theatrical books by now, instead of still running eight shows a week, down on Sullivan Street.

Lore Noto first encountered THE FANTASTICKS as a reading in an acting class and then on a bill of one-acts at Barnard College in 1959. Its director from the outset had been Word Baker who, along with Jones and Schmidt, had been a student at the University of Texas in the early 1950’s. “Tom and Harvey had created something,” Noto recalls, “that I recognized in my own mind as a remarkable artistic achievement. The use of language in The Boy and The Girl’s monologues was so beautiful and so poetic that I was able to trust them, and Word Baker as well, and give them a free hand. I had to have confidence in anyone who could conceive a thing like this.”

Noto’s faith in the three collaborators, and in THE FANTASTICKS itself, represents his idealism and sense of optimism. The middle son of an Italian immigrant, Lorenzo Noto was three when his mother died. He and his brothers were sent to live at the Brooklyn Home for Children by his caring but hard-pressed father. Mr. Noto visited regularly and provided family gatherings on holidays. The facility was his home until the age of sixteen. While there he sang in church choirs and developed his interest in commercial art. He found an apprentice job with a commercial art studio and studied acting at night.

As early as 1939, Noto was working as an actor around New York. “In those days,” he says, “Off Broadway was referred to as Little Theatre, primarily because of playhouse capacity. We performed in churches and New York City libraries doing Chekhov, Ibsen and original plays throughout the five boroughs.” Later, working in the New England area, he wrote and directed short patriotic plays for local YMCA events. Although Lore Noto was 4F due to his eyesight, joined the merchant marine service and became an Able Bodied Seaman. While ashore in Antwerp, Belgium on December 16, 1944 he was gravely wounded in a direct hit of a V2 bomb, and as a result was awarded a Purple Heart by the US Army. When his hitch ended in 1946, he re-entered the commercial art field and married in 1947. Noto and his wife Mary had three children by the time he quit his job to produce THE FANTASTICKS. A fourth came later and by now, all have worked in some capacity with the production.

Noto believes his theatrical success couldn’t have been achieved without his wartime experience. He states, “We all know in comparison to the pain and horror of war, theatre is artifice. But the harsh disciplines I learned taught me the importance of collaboration. Theatre is a collaborative art; showboating is the primary pitfall to be avoided; ‘Stroke oars together’ is a life survival truth. When I was offered the opportunity to produce THE FANTASTICKS, I was well prepared to accept the responsibility of so admirable a venture. I was able to not only recognize, but to trust, the special talents and skills of not merely its creators, but the many in all departments who have served the musical since its inception.”

Noto’s own training as an actor prepared him to “improvise’ as a producer. He continues, “We broke quite a few long-standing theatre customs and practices. We allowed Music Theatre International to release the subsidiary stock rights and allow a television version while we were still running in New York. These are now standard practices in the Off Broadway field.”

For Noto, THE FANTASTICKS is a work that crosses time and generational barriers. “It has a universality that reaches around the world. One song says, ‘Without a hurt, the heart is hollow.’ That’s a fact. Another song says, ‘What at night seems oh so scenic/May be cynic in the light.’ These are statements of philosophy.”

Noto continues, making a point about the musical’s longevity, “All these years we secretly harbored the fear that the talent we’d need for replacements would not be showing up, because the contemporary musical styles ‘were a changin’. We are thrilled to note that the schools, colleges and regional theatres are still providing the New York Stage with talented young artists as capable and willing as before, for if, and only if, that flow continues, can we expect to maintain our reputation for high artistic achievement.”

Remembering back to the beginnings of THE FANTASTICKS he says, “Maybe the coming together of all the elements was foreordained; certainly, the right people, at the right time, with results like these, is not a very common occurrence.” For his part, Lore Noto was given the Alumni Achievement Award by the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in 1966.

“In 1971, it looked as if the show would go under,” Noto admits, “and while I’d understudied The Boy’s Father from the start, I’d never really played it for any length of time. I’d always wanted to be the last Father, so I went in and continued until June 9, 1986!” On that last performance date, also his birthday, Noto attempted to retire himself and THE FANTASTICKS Sullivan Street production. The closing notice caused public disbelief and a spontaneous flood of protest.

“To me it was all the same thing — coming to the end of an era,” Noto says. Seeing that the box office advance sales were particularly good, he felt that this was the time “to go out with style, grace and nobility. Why does a show have to close under the worst conditions? Why not close under the best, during a successful run?”

Lore Noto gave in to such unrelenting pressures as a petition signed by theatre people, a nagging cast and crew, tears on his dressing table and friend Don Thompson. “When Lore told me, I couldn’t believe it,” says Don Thompson. So Donald V. Thompson stepped in, became Co-Producer.

THE FANTASTICKS continued it’s run until it’s final performance on January 13, 2002.

Word Baker

director

Word Baker was born Charles Baker in Honey Grove, Texas, a town of about 2,500 in the northeast comer of the state. He later took on his mother’s maiden name as his first name. After finishing graduate school at the University of Texas at Austin, Baker developed a distinguished career as both a director and a teacher. His academic posts included the theater departments at Carnegie Mellon, Boston, Purdue, Cincinnati and Texas Universities.

Before The Fantastics was even conceived, Baker directed off-Broadway plays in New York including a highly acclaimed revival of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Produced in 1958, Baker’s staging of the drama was hailed by New York Post critic Richard Watts, Jr., as “a finer play than… when first produced in 1953…. The play, in Word Baker’s arena staging, has a simplicity and directness missing from the original production… ‘The Crucible’ tells is terrible story with a growing quality of emotion that is tremendously engrossing.”

Baker’s work with The Crucible was praised by the playwright as well. Both Arthur Miller and his wife, Marilyn Monroe, sent telegrams to the director expressing their admiration for his production.

Baker’s other Off-Broadway shows included The Pinter Plays and I’m Getting My Act Together and Taking It on the Road, and he directed Lillian Gish in the television production of The Glass Menagerie.

When Baker teamed up with his friends Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt on The Fantasticks, he had more input into the show than he had ever had with a professional staging. “It was more than just directing because he was involved in the actual creation of the show,” said his daughter, Lucy Baker. The Fanasticks was his shining moment, he loved everything about it.” Lucy was four when the show opened, and didn’t get to stay up late enough to see the second act until three years later. “I always went with my dad when he would check up on the show,” she recalled. I was seven years old when I finally stayed to see the second act. Before that I always thought the show had a happy ending–seeing the painful parts of the second act for the first time just destroyed me! It was a big thing for me at that age.”

Word’s three daughters grew accustomed to the after-theater parties that got started late at night in their home. “Mom and Dad always had huge a huge party after a new show,” said Lucy. “My father was very social; he loved to host parties and paid enormous attention to every detail from selecting the perfect candles to preparing the food. We girls would be asleep when Dad would wake us up to meet everyone.

Barbara Baker recalled what it was like to grow up with a parent who was a theater person. “We’d put on our pajamas and go up to the school to watch Dad run a rehearsal,” she said. “In those days, just after the war, they didn’t use babysitters. Our parents took us everywhere. We didn’t know that the rest of the world didn’t live like that, bringing the whole family to Dad’s work and letting the kids fall asleep in the theater seats.

“Dad was driven to be excellent at everything he did, not just the theater,” Barbara continued. “He was intense in his work and in his parenting, and he always approached everything in a very creative way. He was involved and helpful with our schoolwork and cared that we got good grades and were good students.

Barbara took part in the first Jones-Schmidt-Baker college collaboration, the “Hipsy-Boo” revue. “I danced in the show,” she said. “We got to be in everything!” Years later Barbara sang the title song from the revue for a sorority event when she was in college.

“When I go to the show in New York now,” said Barbara, “Dad’s touches are still very clear.” Lore Noto often asked him to come and solve a problem or clean something up that had somehow slipped from the original staging. This kept Dad actively involved in the show for years, and he appreciated that. We all found it a treasure to see it just as Dad had envisioned it. There is a kind of comfort in that.”

Perhaps even more important than his staging of The Fantasticks is Word Baker’s legacy as a guiding force for the many students and young actors who worked with him in theater departments and festivals throughout the country. “He was such an inspiration to young people,” said Barbara. “That was his gift-to inspire, motivate and mentor young talent. Dad’s passion and commitment to the theater was contagious, and he was fearless when it came to telling a student, ‘Go out there and do it if that’s what you want to do.”‘

Excerpt from the upcoming book The Fantasticks: The Official Illustrated Biography of the Show by Antonia Felix.

Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt

authors

Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt, creators of THE FANTASTICKS, were inducted in the Theatre Hall of Fame on February 1, 1999. THE FANTASTICKS presented its 16,652nd performances, and began its 41st year on May 3, 2000 at the Sullivan Street Playhouse

Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt wrote “THE FANTASTICKS’ for a summer theatre production at Barnard College. Their relationship began unofficially at the University of Texas in 1950 with a musical revue entitled “HIPSY-BOO!” for which the former wrote comedy sketches and the latter served as musical director.

Neither of the two was planning to become a writer. Jones was a drama student, majoring in play production and Schmidt was studying art with hopes of becoming a commercial artist.

However, HIPSY-BOO!, directed by fellow student Word Baker, was successful. So successful, in fact, that Jones and Schmidt followed it almost immediately with an original book musical, and after that, they began writing songs together on a more or less regular basis.

After graduation, while both of them were serving in the army during the “Korean conflict,” the two continued their informal collaboration by mail, exchanging lyrics and musical tapes back and forth between the camps where they were based. Upon discharge, along with two other University of Texas chums (one of whom, Robert Benton, became an Academy Award-winning film writer and director) the pair came to New York and took the West Side flat which still serves as office and home for composer Schmidt.

The first New York years were more productive for Schmidt than for Jones, who eked out a meager existence “teaching a little bit, conducting a theatre workshop at St. Bartholomew’s Community Club, and trying, unsuccessfully, to become established as a director.” Schmidt, for his part, was becoming widely recognized in the field of commercial art, first as a graphic artist for NBC Television, and then as a freelance illustrator for such magazines as Life, Harpers Bazaar, Sports Illustrated and Fortune.

The two continued writing together, contributing revue material for Julius Monk’s UPSTAIRS-DOWNSTAIRS shows and Ben Bagley’s SHOESTRING REVUES. And in their spare time, they worked on a full-scale musical based on a little-known Rostand play called “LES ROMANESQUES”. The plot, which spoofs “ROMEO AND JULIET” by having the parents invent a feud in order to make their children fall in love, was envisioned by the young writers as a big Broadway show involving two ranches in the southwest, one Anglo and one Spanish.

“We worked on it, very haphazardly, over a period of several years,” says Jones, “trying to take the story and force it into a Rodgers and Hammerstein mold, which is what everybody did in those days.”

“I always imagined everybody on real horses on the stage of the Winter Garden,” adds composer Schmidt. “Eventually,” says Jones, “the whole project just collapsed, our treatment was too heavy, too inflated for the simple little Rostand piece. It seemed hopeless.”

It was at that point, in the summer of 1959, that Word Baker again played a key role in the collaboration. He had been offered a job directing three one-act plays at a summer theatre which the actress Mildred Dunnock was producing at Barnard College. Baker wanted one of them to be a musical and he told his friends that if they could give him a one-act musical version of the Rostand play in three weeks, he would give them a production of it three weeks later. And that is what happened. After years of struggling unsuccessfully with the material, the two writers threw out everything (except a song “Try to Remember”) and, starting from scratch, completed the basis of what is now THE FANTASTICKS in less than three weeks time.

They even returned to the original title. The English version of the Rostand play which they had used as a guide was an obscure one called “THE FANTASTICKS”, written by a woman under the pseudonym George Fleming. It had been introduced to them by one of their college professors, B. Iden Payne, who had directed it in London in 1909 with Mrs. Patrick Campbell as “The Boy” in a breeches part.

Harvey Schmidt in particular, found himself drawn to this title. “We couldn’t come up with a new title,” he admits, “and we liked the way this one looked, with that “k” adding the extra kick.” Clearly the visual artist dwelling alongside the composer in the Schmidt psyche was asserting itself. “It was hard to sell anybody on it,” he remembers, “but since we didn’t have another title, we sort of drifted into using it.”

“We went back to Rostand for inspiration,” says Jones, “because it was smaller and simpler. And yet we used it only as a guidepost, as a map to refer to whenever we got lost. For years we had wanted to try a lot of experiments mixing presentational forms with musical theatre. And since we were no longer aiming for Broadway, we decided to go ahead and attempt all the things we had been dreaming of doing for years. After all, we had nothing to lose.”

Among these experiments, gathered from a wide spectrum of sources, was the use of The Narrator to help them tell the story, and the “invisible” Property Man from the Chinese Theatre. The suggestion of a commedia company on a crude wooden platform was inspired by a City Center production of Goldoni’s “A SERVANT OF TWO MASTERS”, as performed by the famed Piccolo Teatro of Milan. The thought of using the moon for one act and the sun for the other was borrowed from a production John Houseman had directed of Shakespeare’s “A WINTER’S TALE” at Stratford, Connecticut.

In fact, Shakespeare served as a model in more ways than one. “I decided to attempt the whole thing in verse,” Jones explains, “to mix open verse with heavy rhyming and even, upon occasion, doggerel. I tried to let people end scenes with couplets as a sort of flourish. I followed Shakespeare’s device of using a unifying image to glue the whole thing together. In this case, it was vegetation. Seasons. Gardening. Fruition. Harvest. Whenever in doubt, I tried to put in something about vegetation and the seasons. Curious, nobody’s ever noticed it. At least no one ever mentioned it in a review. But it does provide a texture, all the same. It gives a sort of sub-text to this light, romantic tale.”

When their one-act version was produced at Barnard, it attracted enough attention from the world of the professional theatre that Jones and Schmidt were soon placed in the position of having to choose one off-Broadway producer from a field of several viable candidates.

Their choice was Lore Noto who had first encountered fragments of Jones’s script when director Word Baker used it in an acting class. Having heard the brief opening speeches Jones had written for The Boy and The Girl, Noto was drawn to Barnard, where he saw a very early dress rehearsal and determined to mount THE FANTASTICKS for a commercial run.

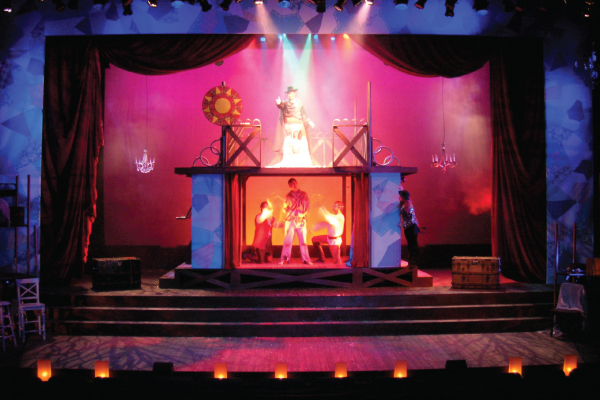

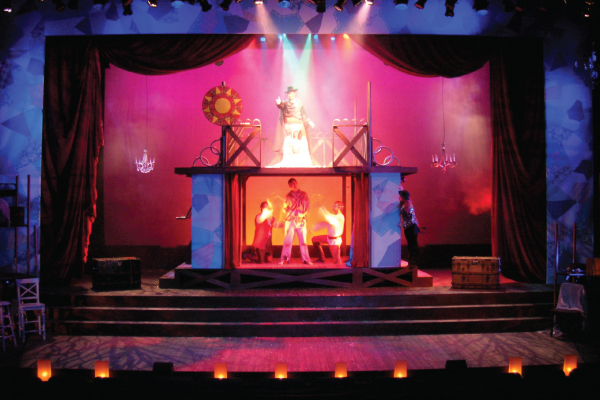

The initial theatre engagement will complete its 40th year of continuous performances at the Sullivan Street Playhouse, the attractive little Greenwich Village theatre where the show opened to rather mixed notices on the night of May 3rd, 1960.

It is to producer Lore Noto that Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt attribute much of the record-making long run of THE FANTASTICKS . “Lore believed in the show when nobody else did,” says Schmidt. “He had total faith in it and it paid off.”

Apart from launching the longest run in the history of the American Theatre, THE FANTASTICKS marked the official New York start of that rich and diverse Jones/Schmidt partnership, a collaboration that until then had been limited to a handful of revue songs.

For Broadway, Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt have written 110 IN THE SHADE, a musical version of N. Richard Nash’s tender Southwest romance, THE RAINMAKER, as well as I DO! I DO!, adapted from Jan de Hartog’s long-run comedy smash, THE FOURPOSTER. For the Jones/Schmidt telling of the famous marital tale, Mary Martin and Robert Preston appeared in the roles originally done in New York by Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn.

For several years Jones and Schmidt worked privately at Portfolio, their theatre workshop, concentrating on small-scale musicals in new and often un-tried forms. The most notable of these efforts were “CELEBRATION,” which moved to Broadway, and PHILEMON, which won an Outer Critics Circle Award.

Along the way they contributed incidental music and lyrics to the off-Broadway play, “COLETTE,” written by Elinor Jones and starring Zoe Caldwell. Later, their full-scale musical based on the same subject toured the western states with Diana Rigg. And later still, it was produced in New York under the title “COLETTE COLLAGE,” where it was recorded by Varese Sarabande with Judy Blazer and Judy Kaye playing the younger and older Colette.

In the 1997-98 season, Jones and Schmidt appeared off-Broadway in “The Show Goes On” a new revue based on their theatre songs. Winning unanimous rave notices and hailed by the New York Times as “lighthearted, loving and sad, laced with nostalgia but also with laughter,” the show extended its run several times and was subsequently released as a CD.

“MIRETTE,” their musical based on the award-winning children’s book, was presented at the Goodspeed Opera House in Connecticut in 1998, and at present they are working on a new western musical entitled “Roadside.”,

In addition to an Obie Award and the 1992 Special Tony for “The Fantasticks,” Jones and Schmidt are the recipients of the prestigious ASCAP-Richard Rodgers Award. In February of 1999 they were inducted into the Broadway Hall of Fame at the Gershwin Theatre, and on May 3rd, 1999, their “stars” were added to the Off-Broadway Walk of Fame outside the Lucille Lortel theatre.

As for “THE FANTASTICKS” as it completes it’s fortieth year at the Sullivan Street Playhouse, it has established its place not only in America, but around the world. Today, this very minute, there are dozens of productions taking place, some in English, some in a wide spectrum of foreign tongues, in such far-away places as Budapest, Bangkok, Beijing and Tokyo, where someone is hanging a cardboard moon and inviting the spectators to “Try to remember, and if you remember, then follow…”

The Fantasticks

presented by Lore Noto on May 3, 1960

Original Cast*

THE MUTE……………………Richard Stauffer

EL GALLO…………………….Jerry Orbach

LUISA……………………………Rita Gardner

MATT…………………………….Kenneth Nelson

HUCKLEBEE…………………William Larsen

BELLOMY……………………..Hugh Thomas

HENRY………………………….Thomas Bruce

MORTIMER………………….George Curley

THE HANDYMAN………..Jay Hampton

THE PIANIST……………….Julian Stein

THE HARPIST……………..Beverly Mann

Directed by WORD BAKER

Musical Director and Arrangements by

JULIAN STEIN

Production Design by ED WITTENSTEIN

Associate Producers

SHELLY BARON, DOROTHY OLIM, ROBERT ALAN GOLD

Lore Noto, theatrical producer, actor and commercial artist, died Monday in New York City. He was 79.

Mr. Noto was best known as the producer of the off-Broadway musical The Fantasticks. The show by author Tom Jones and composer Harvey Schmidt, opened to mixed reviews on May 3, 1960 at the Sullivan Street Playhouse, but the indefatigable Noto kept it running until its audience discovered it, and made it the longest running show in U. S. theatre history. By the time the final curtain was brought down on the production on January 13, 2002, the show had played 17, 162 performances, earning it the title the “World’s Longest Running Musical” in the Guinness Book of Records.

The show won numerous other honors, including an off-Broadway Obie Award, and a special Tony Award in 1992.

Lore Noto was born in Brooklyn, New York on June 9, 1923. Losing his mother as a young child, he was raised at the Brooklyn Home for Children, then in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. During his teen years he helped his widowed father operate a billiard parlor in Ridgewood, but young Noto trained to be a commercial artist. He also took an interest in acting, and began appearing on stages around the city in 1939.

“In those days,” he says, “Off Broadway was referred to as Little Theatre, primarily because of playhouse capacity. We performed in churches and New York City libraries doing Chekhov, Ibsen and original plays throughout the five boroughs.”

When World War II began, Mr. Noto tried to enlist, but was rejected because of his poor eyesight. Instead, he was able to join the merchant marine. While ashore in Antwerp, Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge, he was among those in a building struck by a direct hit by a German V2 rocket, and was gravely wounded. Mr. Noto was among a group of ten men selected to be the first merchant seaman to be awarded the Purple Heart. He later served in New York City as an artist with a U.S. Navy publication, and ended his career in the U.S. Maritime Service as a Chief Petty Officer in 1946.

Noto believed his theatrical success could not have been achieved without his wartime experience. He said, “We all know in comparison to the pain and horror of war, theatre is artifice. But the harsh disciplines I learned taught me the importance of collaboration.

Theatre is a collaborative art; showboating is the primary pitfall to be avoided; ‘Stroke oars together’ is a life survival truth. When I was offered the opportunity to produce THE FANTASTICKS, I was well prepared to accept the responsibility of so admirable a venture. I was able to not only recognize, but to trust, the special talents and skills of not merely its creators, but the many in all departments who have served the musical since its inception.”

He returned to commercial art following the war, and eventually operated his own studio. He found time to perform in many Off-Broadway productions, and began producing in partnership with others. After seeing a Barnard College production of a one-act version of The Fantasticks, Mr. Noto commissioned the authors to expand the work into a full evening of musical theatre. The show he produced ran nearly 42 years at the Sullivan Street Playhouse in Greenwich Village.

When a casting crisis arose in the first few weeks of the run, Mr. Noto stepped into the role of Hucklebee (The Boys Father) briefly. In 1971, stepped into the role again, and went on to perform it until 1986, winning a citation from Guinness, acknowledging a world record of 6,348 performances, longer than of any actor in a single role up to that time.

In 1986, illness forced Mr. Noto to retire from the stage, and he announced that he was closing the show. A storm of protest followed, and he relented. He brought Donald V. Thompson in as co-producer to help with the daily operation of the production. The show finally ended its run earlier this year with a gala farewell performance, with Mr. Noto personally bringing down the final curtain.

Lore Noto is survived by his wife Mary, a talented illustrator in her own right, to whom he has been married since 1947. He is also survived by three sons, Thad, of Gray, Tennessee, Anthony, of New York City, and Jody, of Vancouver, Washington, and a daughter, Janice, of Ossining, New York, and seven grandchildren. The family requests that donations be made to the Salvation Army in lieu of flowers.